Posted on 02.19.18

MVP's contractor ran into environmental problems during construction of other pipelines

Source: http://www.roanoke.com, February 17, 2018

By: Laurence Hammack

A construction company hired to build the Mountain Valley Pipeline worked on three similar projects that were cited by environmental regulators, who found mountainsides turned to muddy slopes and streams clogged with sediment.

A construction company hired to build the Mountain Valley Pipeline worked on three similar projects that were cited by environmental regulators, who found mountainsides turned to muddy slopes and streams clogged with sediment.

The three developers of the natural gas pipelines, two in West Virginia and one in Pennsylvania, failed to comply with plans to control erosion, sediment or industrial waste, according to enforcement actions taken by state regulators.

Precision Pipeline, a Wisconsin company that is a primary contractor for Mountain Valley, played a role in the construction of the earlier projects.

Opponents of the Mountain Valley project fear that the pipeline will bring the same problems to Southwest Virginia, which features mountainous terrain similar to that in West Virginia and Pennsylvania where pipelines were built.

Those worries were heightened by news that the same contractor will be doing the work.

“I have huge concerns about this company being hired,” said Carolyn Reilly, a pipeline opponent who lives along its proposed route in Franklin County.

“There’s already so much distrust with Mountain Valley,” Reilly said. Relying on Precision Pipeline, she said, “just breeds more mistrust.”

Repeated calls and emails to Precision Pipeline were not returned over the past three weeks.

Natalie Cox, a spokeswoman for Mountain Valley, said that Precision has been selected to build the Virginia section of the two-state, 303-mile buried pipeline. The company also will do some work on the project in West Virginia, along with two other contractors.

“The MVP team conducted an extensive evaluation and review process prior to awarding bids to its selected contractors,” Cox wrote in an email.

“The most important message we want to send to landowners and residents in the region is that we’re going to do this the right way,” she wrote of a construction project that already has begun West Virginia and is expected to start soon in Virginia.

Last week, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) gave its final approval for tree cutting and other preliminary work in certain parts of the counties of Giles, Craig, Franklin, Montgomery and Roanoke.

“We value the safety of our employees, contractors and every single person that lives in these communities, and one of our primary goals remains the preservation and protection of the environment,” Cox said.

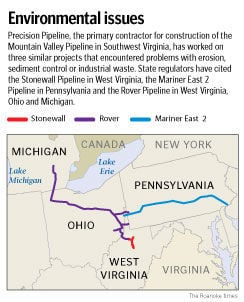

Although Precision Pipeline was involved in three other projects cited for environmental violations — the Stonewall and Rover pipelines in West Virginia and the Mariner East 2 in Pennsylvania — final orders in the cases assign blame to the companies for which it worked. The documents do not spell out details of the contractor’s involvement.

However, Precision is named in notices of violations, inspection reports and lawsuits related to the construction of the pipelines.

Calls starting Jan. 31 and an email to Precision’s headquarters in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, were not returned. A Toledo, Ohio, attorney who represents the company in the lawsuits returned neither calls nor an email sent last week.

Citizens’ fears build as construction looms

In the three years since Mountain Valley announced plans for its $3.7 billion project, which will transport natural gas at high pressure from northern West Virginia to Pittsylvania County, opposition has formed on multiple fronts.

Critics say cutting trees, clearing land and digging trenches for the 42-inch diameter pipe will despoil rural land and waters. They question the need for a pipeline they say will increase the country’s dependence on fossil fuels. And they are angry that a corporate venture will be allowed to commandeer private land along the line’s route, against the wishes of property owners.

Now, with chainsaws and bulldozers being readied, attention has turned to construction.

A key concern is that the work will dislodge sediment that would then be washed away from the work site by rainfall — contaminating streams, private wells and pubic water supplies. Pesticides, herbicides and other chemicals applied to the land over the years could be swept into the toxic mix, opponents say.

There’s little dispute that the risks posed by erosion are greater when a pipeline must traverse steep slopes.

Building the Mountain Valley Pipeline will disturb approximately 5,053 acres of soils that have the potential for severe runoff problems, according to a study by FERC, which gave a key approval to the project and will monitor its construction.

About 67 percent of the pipeline’s route would cross areas susceptible to landslides, the FERC study said, and about 32 percent of the topography includes slopes with a grade of 15 percent or higher.

Mountain Valley has agreed to follow plans to curb erosion and the release of sediment.

However, an environmental impact study by FERC concluded last year that “these plans cannot fully prevent sedimentation, but would provide adequate protections by reducing sedimentation into streams and reducing the potential for slope failures.”

As three pipeline projects in West Virginia and Pennsylvania have demonstrated, no plan is foolproof.

Flooded fields

During the summer of 2015, when the Stonewall Pipeline was being built in West Virginia, landowners along its route began to complain about muddy runoff from heavy rains.

“They flooded our hayfields,” said Robert McClain, who owns a cattle farm in Doddridge County, just downhill from the pipeline construction site.

“They cut swaths in the woods 200 to 300 feet wide, they cut the trees down and bulldozed them into a pile, and they built their pipeline,” McClain said. “We complained to everybody.”

An investigation by the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection found repeated violations that included sediment-laden water contaminating nearby streams, failures to take proper erosion control measures and an “open dump” along the pipeline’s route where drill cuttings and other waste was disposed.

“Stonewall failed to report any noncompliance which may have endangered health or the environment immediately after becoming aware of the circumstances,” an enforcement order from April 2016 stated.

As part of the agreement, pipeline developer Stonewall Gas Gathering LLC agreed to pay a fine of $106,050 and come up with a plan to fix the damage.

Momentum Midstream, the parent company of the pipeline that since has sold the project, said the problems were caused by “several weeks of unusually heavy rainfall.”

“The company worked as quickly as possible at the time to mitigate impacts to property, restore the E&S controls along the pipeline route and reach an amicable agreement with the state to successfully resolve the matter,” Momentum Midstream said in a recent written statement.

The 10-page enforcement order makes no mention of contractors. But the Stonewall Gathering pipeline in West Virginia is listed as one of Precision Pipeline’s projects on the company’s website.

McClain said the company did the work that flooded his land in north central West Virginia. And Precision Pipeline is identified as the contractor in a state inspection report that describes inadequate perimeter controls that allowed the release of sediment-laden water.

Fluid leaks, sediment troubles

The Mariner East pipeline, which runs across the southern length of Pennsylvania, is also listed on Precision’s website as one of its projects.

Last June, the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection issued a notice of violation to the pipeline’s developer, Sunoco Pipeline, and its contractor, Precision Pipeline.

The violation, involving a second phase of the pipeline called Mariner East 2, was for the accidental release of drilling fluid and other industrial waste into wetlands along the pipeline’s route.

A consent order the following month suspended horizontal directional drilling, which involves boring a channel for a pipeline to pass under a stream or river. The ban has since been lifted.

Two years earlier, the department cited Sunoco for allowing sediment-laden storm water to make its way into nearby streams during construction of a different phase of the Mariner East pipeline.

Precision was not named in the state’s final action. But the Pittsburgh Business Times reported at the time that Precision was the contractor, which it attributed to state officials.

Sunoco agreed to pay a fine of $95,366. Since then, Sunoco has merged with Energy Transfer Partners, a company that is building another pipeline for which Precision Pipeline is a contractor.

That project, the Rover Pipeline, is a 715-mile, twin-pipe natural gas project that stretches from West Virginia through Ohio to Michigan. Rover Pipeline LLC was cited by regulators in West Virginia for failing to control erosion, which led to sediment deposits along creek bottoms.

On July 17, 2017, the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection ordered that all work on the pipeline be stopped until its developer could demonstrate its compliance with state regulations. Construction was later allowed to resume.

A spokeswoman for Energy Transfer declined to identify the contractors who worked on the Mariner East and Rover pipelines.

“What I can say is that safety is paramount for any energy infrastructure project we do — the safety of the communities in which we work and operate, the safety of our employees, and the safety of the environment,” Vicki Granado wrote in an email.

On its website, Precision lists the Rover Pipeline as one of its projects. But it describes the work only as painting pipes in Michigan. Before they are buried, most natural gas pipelines are covered with a protective coating to guard against corrosion.

Other documents suggest Precision played a larger role in the Rover construction project.

In reports filed by officials with FERC, which is monitoring work on the pipeline, Precision is mentioned as one of the Rover contractors working in West Virginia.

One report, from November, states that Precision Pipeline’s environmental coordinator told regulators that steps would be taken to reduce sediment release and stabilize a stream bank.

“However, this was not done,” a summary of the violation stated.

Meanwhile, lawsuits in Ohio and Michigan identify Precision as one of the primary contractors for Rover.

The two lawsuits were filed by landowners who claimed that construction crews broke agreements to contain their work to a right of way, pumping water and waste material from an open trench onto areas outside of the work zone.

In one of the lawsuits, Mark and Linda Selby of Dexter, Michigan, accuse Precision Pipeline and Rover Pipeline LLC of diverting thousands of gallons of storm runoff onto their farm land, damaging sensitive soil in which they grow blueberries.

A similar claim was made by landowners in Wood County, Ohio.

In court filings, Precision has denied all the allegations — including the assertions that the plaintiffs are landowners and that it was a Rover contractor. The lawsuits are pending.

Accountability ‘lacking’

When a pipeline project runs afoul of state regulations aimed at preventing erosion and other problems, it’s usually the company that owns and operates the venture — not the contractor it hires to build it — that winds up in trouble.

“If there’s an operating company that invests the money and will operate the pipeline, the accountability ultimately falls with them,” said Carl Weimer, executive director of Pipeline Safety Trust, a nonprofit group that promotes pipeline safety through education and advocacy.

Erosion and sediment control plans are approved by state regulators — one for the Mountain Valley Pipeline is still under review — who issue permits to the companies.

“The rules are the same, and it’s the operating company that is on the hook to make sure the subcontractors are following the rules,” Weimer said.

Once pipelines are built, their operation is regulated by the U.S. Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration. The agency keeps detailed records of leaks and other accidents, which can be searched online by the name of the pipeline operator.

There appears to be no similar system for contractors.

“I think the accountability and transparency is lacking,” said Angie Rosser, who as executive director of the West Virginia Rivers Association has been tracking pipeline construction in the Mountain State.

“What I hear from the big companies is that they are very environmentally responsible, and they make that a priority,” she said. “But where the rubber hits the road, where the damage happens, is with the contractors that they hire.”

The spokeswoman for Mountain Valley stressed that the company will keep a close watch on its contractors.

“MVP demands a high level of performance from its contractors and has planned for an extremely high level of external oversight and monitoring during the construction process,” Cox wrote in an email.

Cox, who asks that all questions about the project be submitted in writing, did not provide a direct response when asked if Mountain Valley knew about the other pipelines involving Precision that have been cited by environmental regulators.

“I think that’s something that would certainly be a red flag, and the owner of the pipeline ought to look into that,” Weimer said.

Precision Pipeline has an environmental plan that it follows to minimize erosion and sediment flow from its projects, according to its website. The goal is “to preserve the integrity of environmentally sensitive areas and to maintain existing water quality,” it says.

For people like McClain who live along the pipeline’s path, those assurances ring hollow.

The Stonewall pipeline that caused so much trouble for him is now operational, and the erosion problems it caused during construction are not as severe.

But now, he said, plans call for the Mountain Valley Pipeline to be built about 400 feet from his home.

“They just keep coming back,” he said of the pipelines that crisscross the West Virginia countryside. “You’re never rid of them. Once they’re on your land, they’re there forever.”

News researcher Belinda Harris contributed to this report.